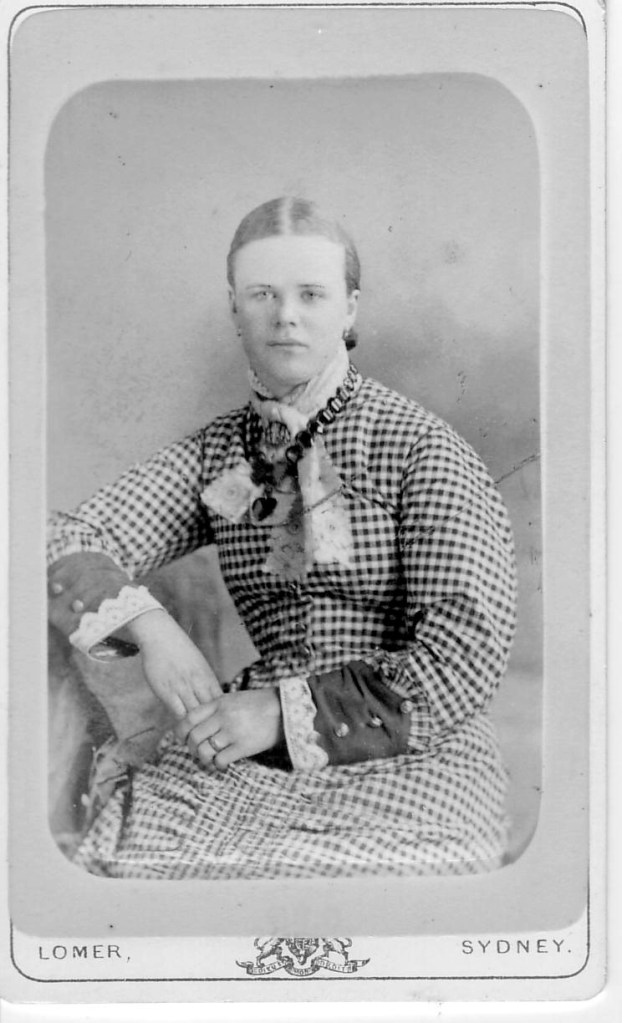

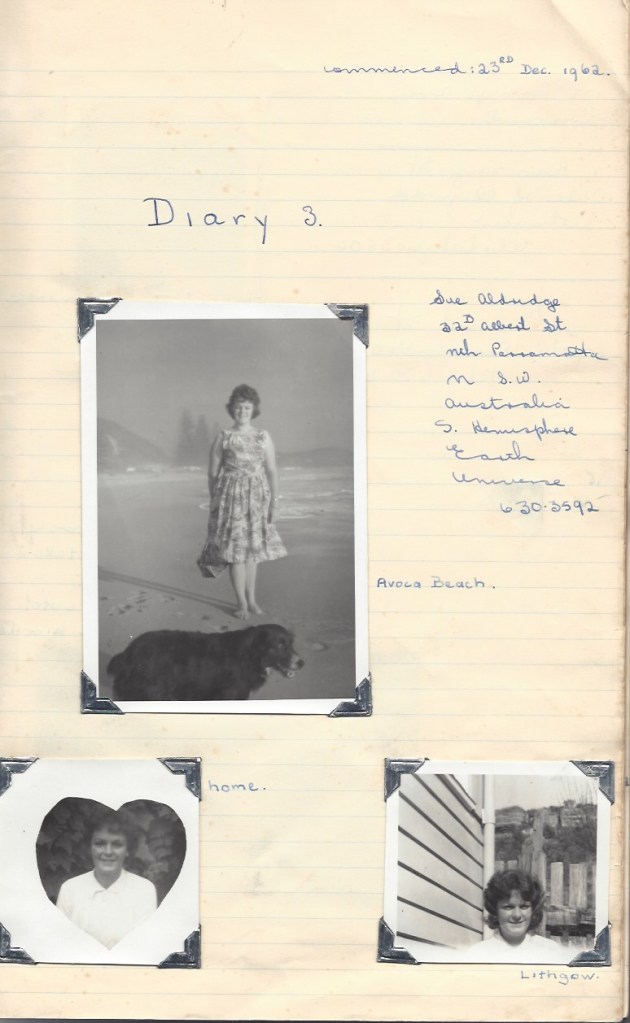

Sarah’s Journey

FROM THE SLUMS OF BRISTOL TO A NEW LIFE IN AUSTRALIA

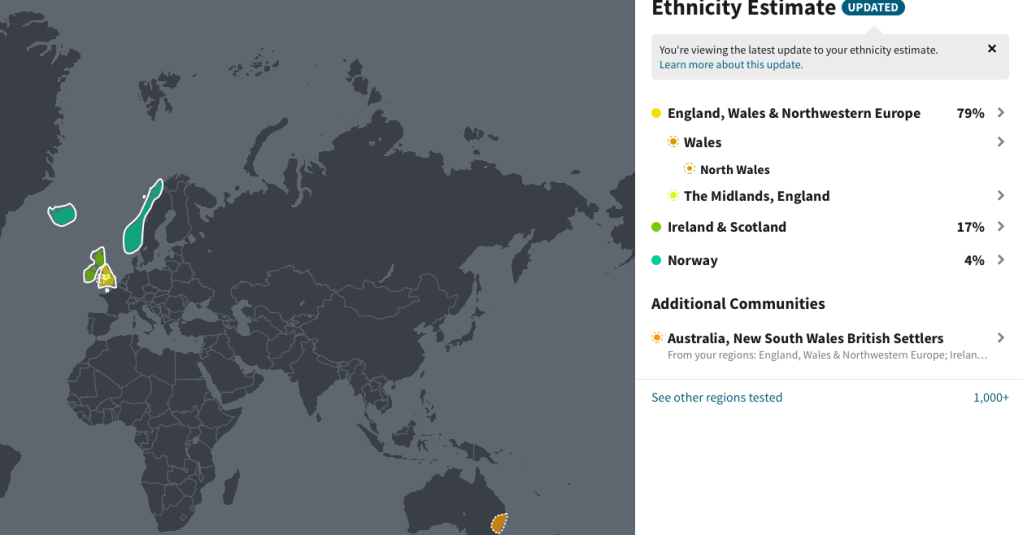

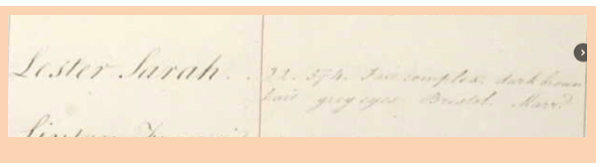

Sarah Lester was most likely born in the slums of Bristol, in 1779. She became a young felon on the streets of London; detained and tried twice at the old Bailey. Her life changed dramatically following transportation from London to Port Jackson, aboard HMS ‘Glatton’, to the challenges, hardships and opportunities to be experienced in her new homeland

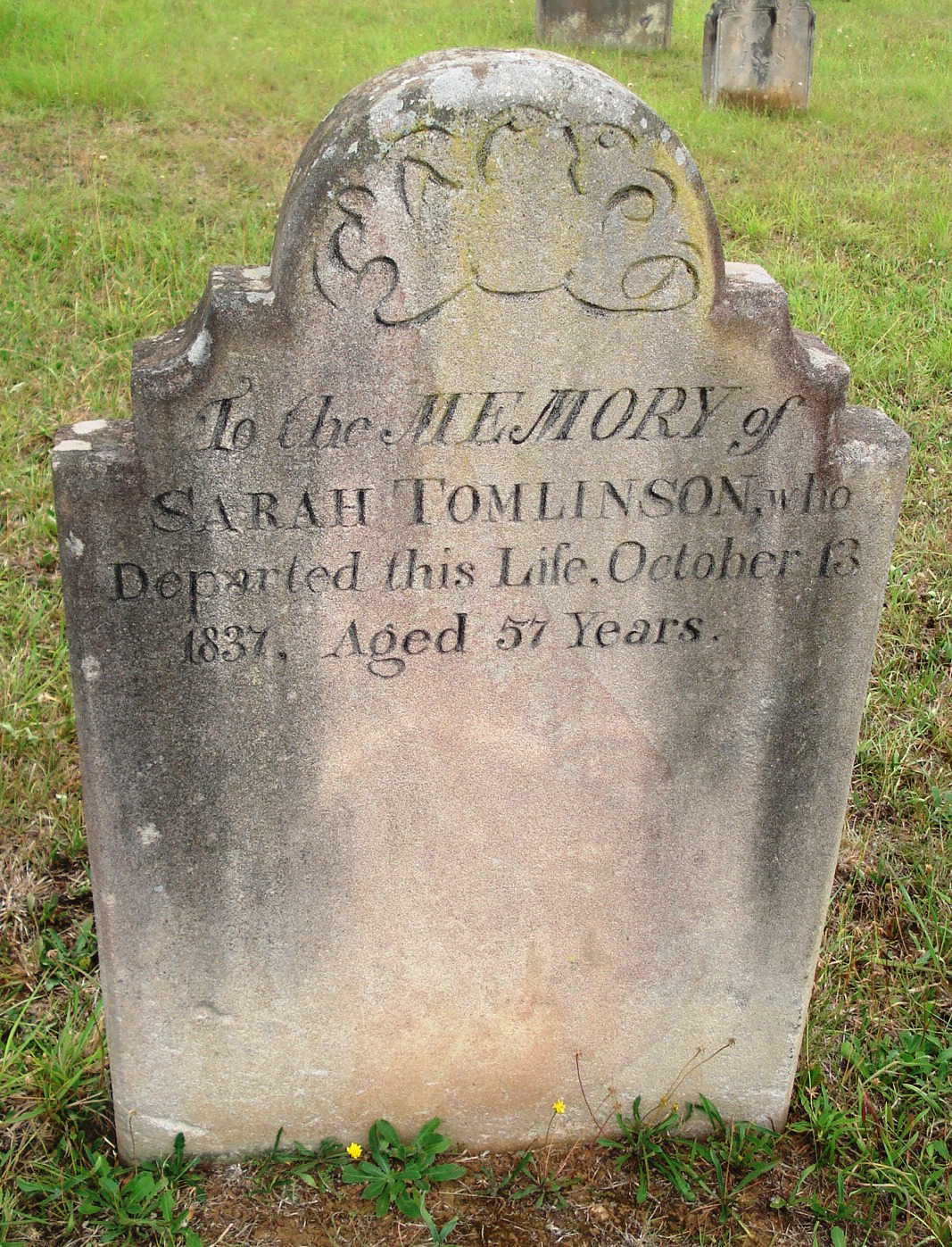

Details about her age vary from the Old Bailey Trials[1] to the New South Wales Convict Musters[2]. It would seem that not even Sarah was sure about her age. In 1837 on her head stone, her age is 57 years, making her birth year 1880.

She was unlikely to have married, as was suggested above. There are no records available of a marriage between a female named ‘Sarah’ and a male named ‘Lester’ within an appropriate time frame in the Bristol area or further afield.

1779 – 1800 Early Days in Bristol

During Sarah’s early life in Bristol, there was social unrest in the city. Rising food costs and industrialisation of the weaving industry led to riots in the streets. The population of Bristol had increased rapidly from about 25,000 in 1700 to 68,000 in 1801[3]. Another aspect was the imposition of Turnpikes and bridge tolls. Notably in 1793 the Bristol Bridge Riot left 11 people killed and 45 injured. [4]At some time during her late teens to early twenties, Sarah moved from Bristol to London.

1801 Trials and Tribulations

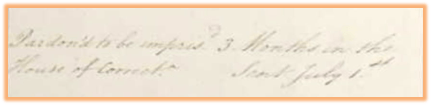

By 1801, Sarah was employed as a Servant to publican, James Tims and his wife, Ann, in their ‘dwelling house’ in London. In early April, Sarah left the Tims’ without giving any notice. Soon after, on 4 April, Mrs Tims discovered that her cloak and two yards of cotton were missing from a locked box. The items were later located at the pawnbroker, Thomas Brown’s shop. Sarah found herself before Lord Chief Baron at Middlesex on April 15th[5]. In her defense, she claimed “I did not steal these things; I picked them up”. She was found guilty and sentenced to death. Fortunately she was pardoned from the death sentence.[6]

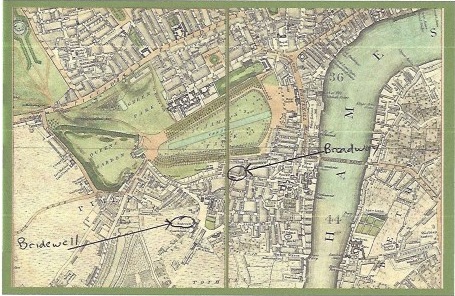

On 1st July, she was committed to the Tothill Fields Prison[7] in Westminster, often referred to as ‘Bridewell’. The building originally was King Henry VIII’s ‘Bridewell Palace’. Conditions in Tothill Fields Prison were said to be less harsh than other establishments, and prisoners were given access to medical care. [8]

During her three months incarceration it is unlikely that Sarah was harshly treated or punished. At the end of her sentence in early October, she was cast out onto the streets possibly without ongoing support or shelter.

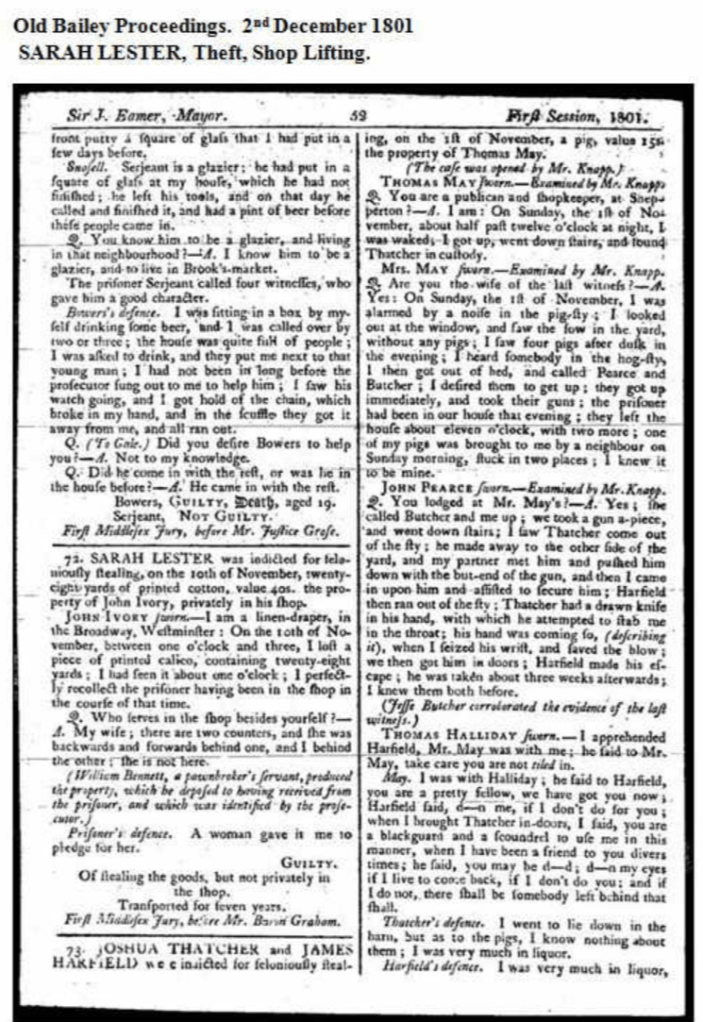

In less than two months, on 26th November, she was again committed to Tothill Fields, charged with feloniously stealing 28 yards of printed cotton from the Drapery shop of John Ivory in the Broadway. [9] The Broadway is not far from where she had so recently been released.

Figure 3 Cary’s New and Accurate Plan of London and Westminster 1795 mapco.net/london

In her defence to Mr Baron Graham at her trial on 22 December, Sarah claimed “A woman gave it me to pledge for her.” [10]She was found guilty “of stealing the goods, but not privately in the shop” and sentenced to be transported for seven years.

1802 Transportation

On 6th September 1802 Sarah was delivered from the Tothill Fields Prison to ‘HMS Glatton’, along with 270 male and 134 female convicts, and about 30 Free Settlers. They departed from England on 23 September and sailed via Rio de Janeiro to Port Jackson. During the voyage 7 male convicts and 5 females died.

On 19 March 1803, it was reported that “the day before she (Glatton) got into the Cove 100 weak people were taken out and put on board the Supply, … their complaints were slightly scorbutic…”. [11] I cannot find any records of Sarah being amongst those passengers. It would appear that she arrived in the colony in a reasonably healthy condition.

1803-1806 Early Life in the Colony

It is likely that soon after stepping foot in the Colony, Sarah was sent to the Parramatta Female Factory beside the Parramatta River. The first record of her, the 1806 Muster, records ‘Sarah ‘Lister’ from the Glatton, a prisoner, employed at the factory at Parramatta.’ [12]

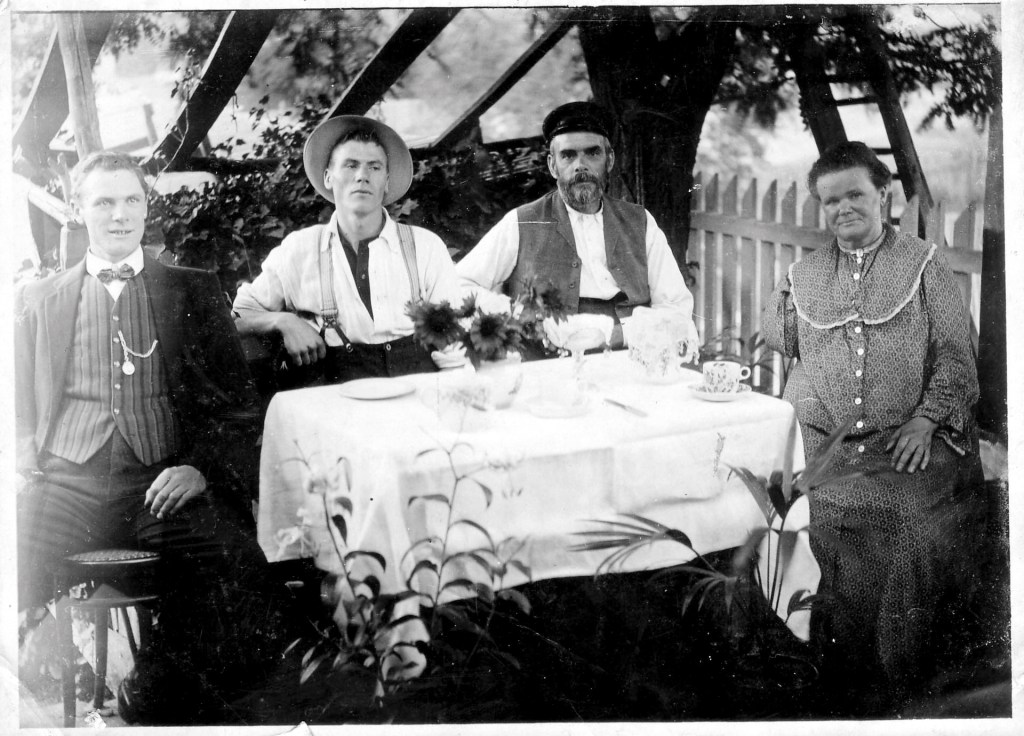

1806-1837 Family Life and Beyond

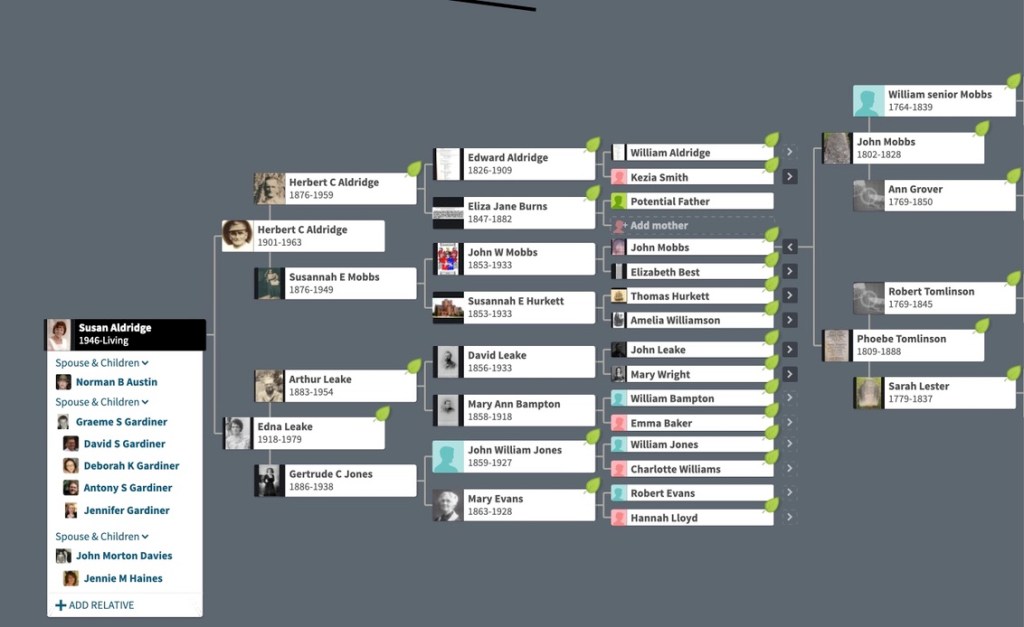

On 15 May in that year her first daughter, Ann Tomlinson was born in Parramatta. [13] The father, Robert, was a convict who had arrived on the ‘Canada’ in 1801. His sentence had expired in1802[14]. He was employed by the Government as a file cutter, and paid a salary of £15.0.0 a quarter from the police fund. [15]

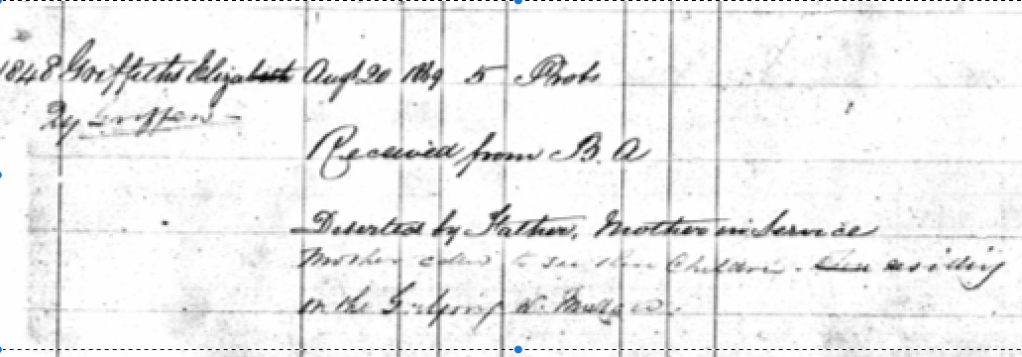

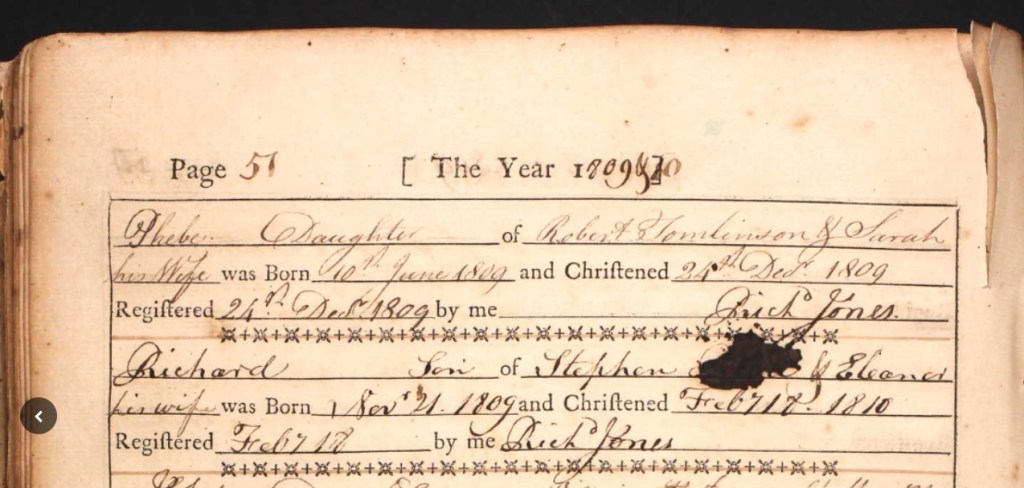

I cannot find any record of permission being granted for the couple to marry; or of the couple having ever married. Sarah and Robert had another two daughters, Phoebe[16], born and died in 1807, and my three times great grandmother, Phebe[17](known as Phoebe) born on 10 July 1809. Both Phebe and Ann were baptised at Saint John’s Church, Parramatta, on Christmas Eve, 1809.

Figure 4 St John’s Parramatta, Baptisms 1809, Phebe Tomlinson

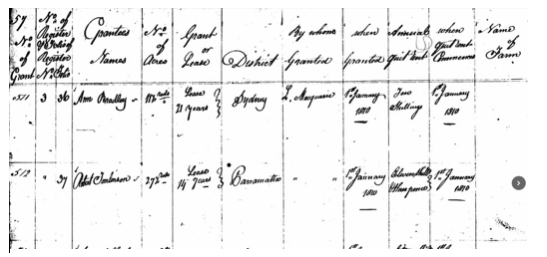

On 1st January 1810, Governor Lachlan Macquarie granted Robert a lease of 14 acres of land in Parramatta for which he paid 11/3d.[18]

Figure 5 Copy of Grant of Lease to Robert Tomlinson

There are no Criminal records for Sarah in the Colony, and she was granted a Pardon 1811[19]. The couple settled down into a life dedicated to making a secure home for their family, with hard work and commitment to their community.

In an obituary to Ann Mobbs (Tomlinson), memories of her father living in a cottage in what was later known as Parramatta Park are mentioned. [20] It is likely that this was the allotment granted to him in 1810.

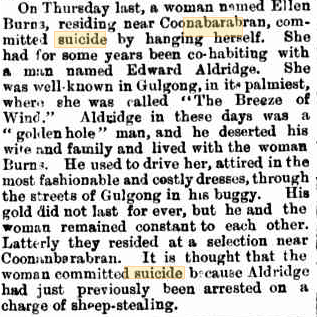

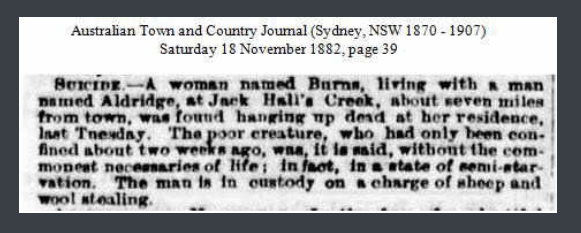

Figure 6 “The Late Mrs Mobbs”

Ann also reflected on tales of “travellers waylaid, robbed and even murdered; revolts among the convicts; and attacks by the blacks were so common as to excite little but feelings of thankfulness amongst the more fortunate that they had so far escaped molestation.” Sarah must have seen and experienced many challenging and frightening events raising her family in Parramatta.

Sarah’s journey ended with her death on October 13th 1837. She is buried in the St John’s Cemetery, Parramatta.

Bibliography

Bateson, Charles, ‘The Convict Ships 1787 – 1868’ Library of Australian History, Sydney, NSW. 1983.

London Lives 1690-1800 – Crime, Poverty and Social Policy in the Metropolis, ‘Bridewell Prison and Hospital’ https://www.londonlives.org/static/Bridewell.jsp , Accessed 17 May 2018-05-29

Jones, Philip D. (1980). ”The Bristol Bridge Riot and its Antecedents: Eighteenth-Century Perception of the Crowd”. Journal of British Studies, 19(2), 74-92. Doi:10.1086/385756. Accessed 17 May 2018

Mapco, Map and Plan Collection Online, London and Environs Maps and Views, http://mapco.net/london.htm. Accessed 23 May 2018.

Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org.version 6.0, 17 April 2011), April 1801 trial of Sarah Lester (t18010415-75) Accessed 20th May 2018

‘Old and New London: Volume 4, Westminster”, Tothill Fields and neighbourhood Pages 14-26 Originally published by Cassel, Petter and Galpinm London, 1878, available at: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol4/pp14-26, Accessed 17 May 2018.

Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org.version 6.0, 17 April 2011), December 1801 trial of Sarah Lester (t18011202-72), Accessed 20th May 2018.

Parramatta Heritage Centre, ‘The First Female Factory, Prince Alfred Square, 1803-1821’, 12 August 2015, (http://arc.parracity.nsw.gov.au/blog/2015/08/12/the-first-female-factory-prince-alfred-square-1803-1821/ ) Accessed 9 May 2

The Digital Panopticon Sarah Lester , Life Archive ID obpt18011202-72-defend617 (https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpt18011202-72-defend617, Accessed 28th May 2018.

‘The Late Mrs Mobbs’, Australian Town and Country Journal, (Sydney, NSW: 1870-1907) 27 December 1890, Available on Trove, https://trove.nla.gov.au, Accessed 27 May 2018.

1811-1870 New South Wales, Australia, Land Records, Ancestry, Accessed 19 May 2018Acces.

‘1806–1849 New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, Ancestry, Accessed 18 May 2018.

‘1790-1849 New South Wales, Australia Convict Ship Muster Rolls and Related Records’, Ancestry, Accessed 21 May 2018.

‘1788-1842 Australia, List of Convicts with Particulars’, Ancestry, Accessed 18 May 2018.

1791-1867 Australia Convict conditional and absolute pardons, Findymypast, Accessed22 May 2018.

1792-1981 Australia, Births and Baptisms, Ancestry, Accessed 21 May 2018.

[1] Old Bailey Proceedings Online, Trials of Sarah Lester, (t18010415-75), (t18011202-72) Accessed 20 May 2018.

[2] Ancestry, Muster Records for Sarah Lester, ‘New South Wales and Tasmania, Australia Convict Musters, 1806-1849’, Home Office: Settlers and Convicts, New South Wales and Tasmania, National Archives, Kew, Surrey, England , Accessed 18 May 2018.

[3] Localhistories, ‘A Brief History of Bristol, England’, Accessed 17 May 2018.

[4] Journal of British Studies, ‘The Bristol Bridge Riot and Its Antecedents: Eighteenth-Century Perception of the Crowd’, Philip D. Jones, http://lydia.bradley.edu/academics/las/civ/bristol, accessed 17 May 2018

[5] Old Bailey Proceedings Online, Trials of Sarah Lester.

[6]The Digital Panopticon Sarah Lester, ‘Life Archive ID obpt18010415-75-defend816’ (https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpt18010415-75-defend816 , Accessed 27th May 2018).

[7] Britishhistory, ‘The City of Westminster, Introduction’, Old and New London: Volume 4 (1878), Accessed 17 May 2018.

[8] Londonlives, ‘Bridewell Prison and Hospital’, https://www.londonlives.org/static/Bridewell.jsp, Accessed 17 May 2018

[9] Ancestry, England and Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892 for Sarah Lester, Home Office: Criminal Registers, Middlesex HO 26; Piece 8; Page: 78, Accessed 20 May 2018.

[10] Old Bailey Proceedings online, Trials of Sarah Lester .

[11] ‘Ship News’, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 19 March 1803. P. 3.

[12] Ancestry, Muster Record for Sarah ‘Lister’.

[13] Findmypast, Birth Transcription for Ann Tomlinson. ‘New South Wales Births’, Accessed 21 May 2018.

[14] Ancestry, Muster Record for Robert Tomlinson, ‘State Records Authority of New South Wales; Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia; Title: Muster of Prisoners in the Colony, 1810-1820; Volume: 4/1237’ Accessed 28 May 2018

[15] Ancestry, Salary Robert Tomlinson, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Colonial Secretary’s Papers, 1788-1856, Special Bundles, 1794-1825’, NRS 898; Reels 6020-6040; Fiche 3260-3312, Accessed 27 May 2018.

[16] Findmypast, Birth Transcription for Phoebe Tomlinson,(New South Wales Deaths 1788-1945 Transcription V18072152 2A), Accessed 21 May 2018.

[17] Ancestry, ‘Birth Index, 1788-1922 New South Wales, Australia’, (Phebe Tomlinson) V1809604 148, Accessed 21 May 2018.

[18] Ancestry, Land Grant for Robert Tomlinson, ‘New South Wales, Australia, Registers of Land Grants and Leases 1792 – 1867’, Accessed 30 May 2018.

[19] Findmypast, Australia, Absolute Pardon for Sarah Lester, ‘Convict Conditional and Absolute Pardons’, 1791-1867, Accessed 21 May 2018.

[20] ‘The Late Mrs Mobbs” ‘Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney. NSW)’, 27 December 1890 Page 32, Accessed 22 May 2018.