The Blue Mountains were a significant barrier to the development of rail travel to the west of NSW. The railway line had only reached Lithgow in 1869, following the construction of the section known as the ‘Zig Zag’ built to allow the steam trains to descend the steep terrain leading down into the Lithgow Valley from the western side of the mountains. In the early 1860’s the ‘Little’ Zig Zag, or Lapstone Zig Zag had been constructed to climb the eastern side of the Blue Mountains. It took the steam locomotives about 6 hours to haul the train from Sydney up to Lithgow.

The same year that Mary Ann and David travelled up to Lithgow, a lyrical report written by a subscriber identified as C.H.W.H’ was published in the Sydney Daily Telegraph on 18 September 1880, page 6. :

“From the moment that those charming suburbs, Ashfield, Croydon, Burwood and Homebush, are reached until the train stops at the end of its destination through the mountains, the eye of the traveller revels in scenes picturesque and sublimely beautiful.”

It was probably the day after their wedding that Mary Ann, dressed in her travelling outfit similar to the photo below and David made their way to the Railway terminal known as Redfern.

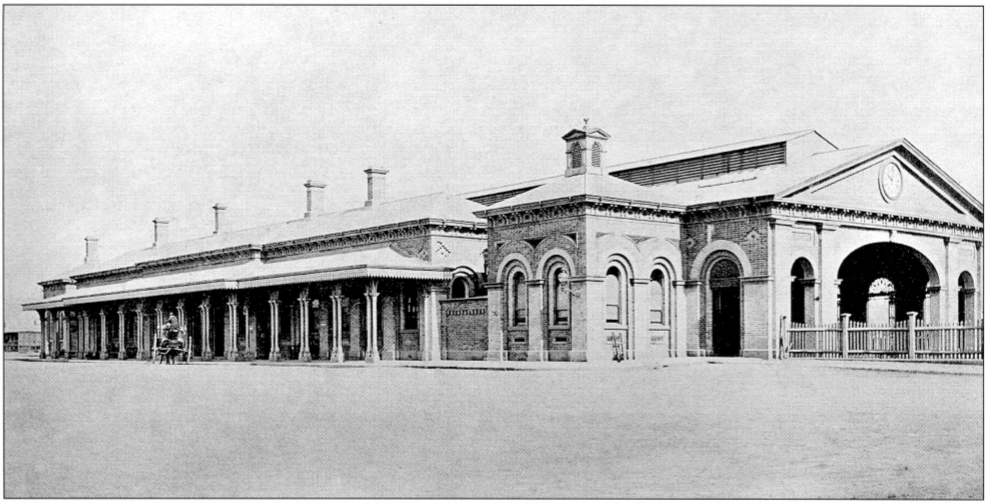

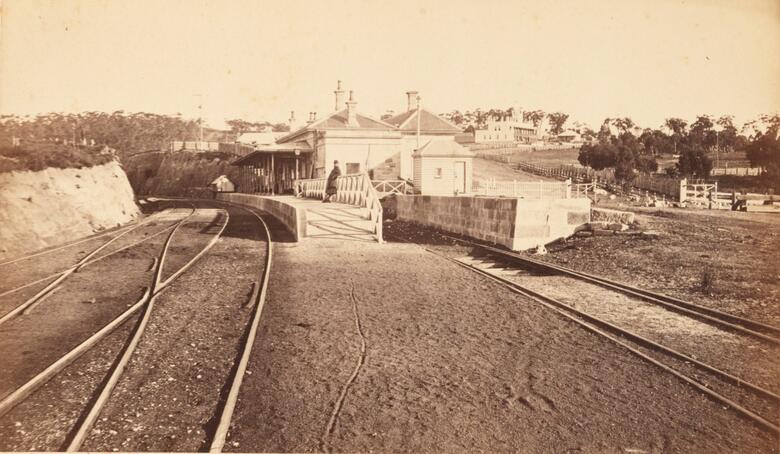

They may have hired a horse and buggy driver to transport Mary Ann’s trunk and other luggage to the station. The impressive brick and stone building had been built in 1874 on the site of the original temporary tin shed terminal located in the Government Paddocks between Devonshire and Cleveland Streets.Although it was sometimes referred to as ‘Redfern Station’, it was located to the northern boundary of Redfern.

Eastern Side (departure side) of the second Sydney railway station c 1879 NSW State Archives and Records

The train was at the platform when Mary and David arrived at the station . They were met by a porter dressed in a smart railway uniform., who efficiently relieved them of their luggage and wheeled it away on a trolley, to be stowed in the luggage carriage at the rear of the train.

David took her elbow and helped his wife up into the second class carriage. Waiting for the last leg of her long journey to begin, Mary Ann gazed out of the window taking in the vision of the recently completed platform. She thought how fitting it was that her epic journey had begun and ended in a steam train. Promptly at 9am, with a throaty whistle followed by the chuffing sound of steam, the mighty locomotive slowly rolled out of the station

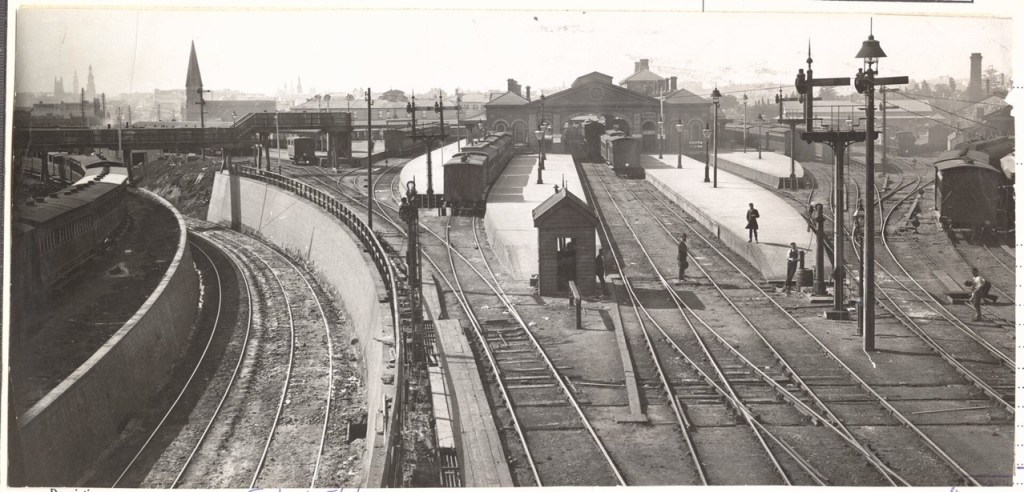

Second Sydney Sydney, terminal, 1884. State Archives Collection NRS-17420-2-25-842/042

The train proceeded rapidly through the inner suburbs of Newtown, Ashfield Burwood and Redmyre (later Strathfield) with views of the back yards of many homes built beside the railway line.

NEWTOWN

ASHFIELD

‘C.W.H’ described the landscape near Parramatta as:

“orchards, flower-gardens and orange groves shed their bloom; and, as the train flies through this cultivated locality, odours, of orange flower and spice greet one from time to time,.”

At the time that Mary Ann passed through, the orange trees may have been laden with golden fruit.

PARRAMATTA

As they proceeded further westwards, from Parramatta to Penrith, the country side became less and less densely inhabited, with scattered villages along the way; a yineyard, and paddocks with market gardens, chickens, cattle and horses grazing.

BLACKTOWN

At Blacktown the first glimpses of the distant Blue Mountains appeared

“shrouded in ethereal loveliness, rising tier upon tier, robed in royal purple…bedizened with golden sunshine streaming down upon them from cloudless skies, their deep gorges, ravines and valleys enveloped in mystic shadow..”.reported C.H.W.H on page 6 in the Daily Telegraph 18 September 1880:

ROOTY HILL

After having travelled some thirty seven miles (about 60 kilometres) the train pulled into Penrith Railway Station.

PENRITH

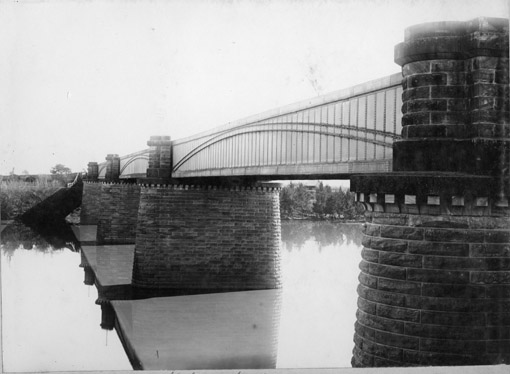

Soon after leaving Penrith they rattled over the Victoria Bridge across the Nepean River at the foot of the Blue Mountains Ridge. Over the metal sides of the bridge, Mary Ann caught glimpses of the river, studded on either side of its banks with comfortable dwellings, surrounded with orchards and large areas of cultivated land.

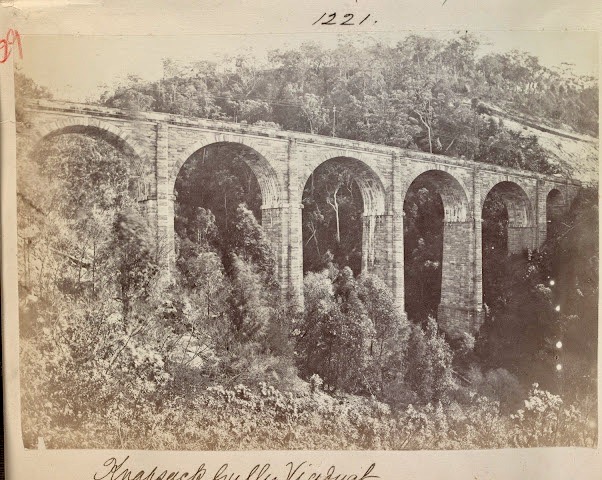

On the other side of the river, approaching the ‘Little Zig Zag from Emu Plains, Mary Ann caught her breath in awe as she glimpsed the impressive stone viaduct over Knapsack Gully ahead to her left..

KNAPSACK GULLY Viaduct Emu Plains 1877c State Library of Victoria

Pulling the train up the steep incline to the “Blue Mountains” the engine worked very hard. In an article published on page 22 in the Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney NSW) on 22 November 1879, a ‘Special Reporter’ described their experience

“Higher and higher we mount the ranges, on many points of which have been build nice cottages and mansions, which during the summer months are occupied by many of the leading families of the colony, who seek in the pure mountains air a healthy restorative… On either side of the line the trees are sending forth new shoots; the various kinds of eucalypti are budding; the undergrowth is full of beautiful and variegated flowers, amongst which the noble Waratah is conspicuous …”

Mary Ann would also have seen swaths of rocky, scrubby, dry country and enjoyed glimpses of impressively scenic. rocky gorges, with tree ferns, mosses and maiden hair ferns growing in the damper shadier gorges. It would have felt so unfamiliar and at times challenging.

On page 88 in the Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser dated 20 July 1878 a cpmntiobiuter by the name of ‘The Sketcher’ described their experience as follows:

“The Blue Mountain line is very tortuous. We go in all directions; sometimes the sun is on the right side and sometimes on the left, as we sweep along the sharp curves, the presence of which the traveller is uncomfortably made aware by being swung off his legs if he happens to be standing. This mountain railroad is wonderfully level when we consider that it leads us at least to a height of more than 3000 feet above sea level, and, excepting on the zigzags, if a person were to walk it he would not find the ascent the least burdensome. Still up we go, though we hardly know it, the faithful telegraph wires keeping us company. Glimpses of stupendous scenery are faithfully caught as we speed along, to be lost again as the grand panorama unrolls itself before the eye. No sooner do we settle down to survey some of the wildest scenes in nature than a jutting rock, or the section of a cutting, provokingly shuts all from view, and we are left to meditate, as best we can, on a disappointment which represents many other things in life. Stately forest trees, as at Springwood, indicate the richness of the soil; beautiful wild flowers, such as epacris and aoacia, even now lift up their heads in the pure mountain air ; mosses and ferns abound as we advance upward, and swamps now and then appear which seem to have no outlet. We pass the head waters of many a grim gully sloping rapidly downward from beneath our feet, and soon lost to sight in the gloomy depths of the gum trees, over the leafy crown of which the eye travels far, until bounded in the distance by a deep shade of blue. At Katoomba station one of the two engines that dragged our train was left behind, its services being no longer required

Further in the article published in the Sydney Daily Telegraph in September 1880, C.H.W.H reported: upon reaching Katoomba:

“At Katoomba there is nothing in the form of an inn or other public house …. whatever. At all but one of the other stations on the line there are – although many of them are of the rudest description. and the charges for their use exorbitantly high. Blackheath is the next station to Katoomba. Here a platform is the only accommodation for passengers entering or leaving the train. A great many persons stop at this place for the purpose of visiting Govet’s Leap … Govet’s Lcap is about four miles from the railway station, and six miles from Mount Vittoria as it was named — Victoria, it is called. Of Govet’s Leap wild tales are told. This is of course, to heighten the interest attaching to the spot. One of the stories related to me by a mountaineer is quite sensational. It is as follows:-in the days when New South Wales was the reservoir of European convicts, a desperate criminal, laden with fetters, escaped from imprisonment and made his way to the Blue Mountains. He was pursued and overtaken at the pass now celebrated as Govet’s Leap. To avoid recapture, so the story goes, this daring man leapt into the abyss and was never heard of or seen afterwards. Another tale, much more probably the true one asserts that a surveyor named Govet came so suddenly upon this inaccessible mountain gorge that he would have fallen, headlong down the precipice had he not taken a desperate leap on to an intervening crag and to perpetuate this act of bravery his companion named the spot Covet’s Leap.”

I wonder if David knew that tale and shared it with Mary Ann as they continued on their way.

Arriving at Mt Victoria at about 2pm, the train paused for about 20 minutes to allow the probably famished passengers to have something to eat at the refreshment rooms on the station. Although, given the short time and number of passengers not everybody may have been served in that time. In the Sydney Mail, 20 July 1878 a contributor referred to as ‘The Sketcher’ reported on page 88 that:

“A tidy refreshment-room close to the station afforded every accommodation that was needed. But, through the rush being greater than perhaps it was expected to be, the attendance of the waiters was not so brisk as it might have been, and I soon found that I should have to dine on atmospheric air, if I had not waylaid a waiter and served myself. “

Mt Victoria Station 1879 extended to include refreshment room SLNSW PXA1109-15 – Mount Victoria Station

C.H.W.H concluded their article in the Telegraph with a deeply felt account of the descent via the Zig Zag into the Lithgow Valley:

“A few miles journey from the Mount brings the traveller to the far famed Zig Zag beginning with the viaduct, above Clarence tunnel, placed at an altitude of seven hundred feet above the level of the valley in which it begins. Clarence’s Tunnel is a quarter of a mile in length. The circuitous descent from the mountain side has a very singular effect upon the traveler’s nervous system: per perpetually winding and whirling as it seems now hanging on the extreme verge of the mountain gorge, where the slightest deviation from the narrow and precipitous way would hurl the train into an abyss hundreds of feet below, which certain destruction would be more to follow an occasion some trouble in the gazer’s mind. The vibratory motion from the continual shunting of the train, necessary to the sinking from one line to another is extremely disagreeable -the banging and a sense of falling being most unpleasant. There are two tunnels on the ZigZag.

The level of the valley below the Zigzag gained, a steam of about 20 minutes brings the train into Litbgow, and 10 minutes more to Bowenfells station. The scenery through which the Zig Zag winds, is some of the grandest on the Blue Mountains. The winding valley is enclosed in tremendous walls and jutting crags of solid rock between the fissures of which grow the most magnificent trees and shrubs to be found in this wilderness teeming with the beautiful. The flora of the Blue Mountains are magnificent and various, and here about the Zig-zag the most splendid specimens abound. It has been said that these flowers are without perfume, but it is a mistake. The air is often fragrant with their delicious odours. The zoology these wilds comprises only opossums, wild cats, rats, and of birds, magpies, cockatoos and kingfishers “

After such a dramatic conclusion to her journey, I imagine that Mary Ann must have felt immensely relieved to finally have reached her destination. Now it was time for her to truely begin the next part of her life and join her husband in setting up their home together in the Vale of Clwydd.